It was cold on the edge of 1984. Dread swamped around frayed hems, an ominous puddle stagnating as the year loomed closer, then subsiding as the new year broke and that dumfungled vision of a jackboot future forever stalled, mired at the sluice gates neath the ruined towers on the edge of town.

The young folks in the city and satellites of Manchester shook off Orwellian glooms and stepped out in unexpected joys, in Brogues, Loafers, Chelsea boots, Oxfords, Gibsons, Boat shoes, White Stilletos, Doc Marten boots, Winkle Pickers, Dunlop Green Flash, Espadrilles, Chinese slippers, Galoshes, Steelies and all manner of grifted and grafted trainers that poured all over the markets like farmed fish, marching and dancing the new year into form.

1984 was already set for turmoil. Britain was at war with its workers and the pop cultural tribes were colliding and cross pollinating in the cracks of this broken British landscape. I was 15 years, 5 months old as the year began and our old man had just left his job.

1983 had been a busy and successful year for him, he’d started a new job in the music industry which took him out of town and he wasn’t always as available on weekends when we habitually had spent time with him, but we saw him at unusual times too as his new work was less bound to standard daytime working routines. He was on fire back then in ’83, constantly generating energy into ideas as a pivotal character in this very driven group of people in and around The Smithss, a gathering of energies which for a spell was enchanting the nation. As 1984 broke he quit this job, quite unexpectedly from our perspective. There was a cloud of unknowing around and about it all and a cringeingly obvious discomfort which we couldn’t talk about. I accepted the explanation offered that it was all for ‘family reasons’ although that was clearly a deflection. The year shaped up soon enough and Joe Moss swung back to his old business of making clothes and vibes back at the Crazy Face factory on Portland Street.

He was often given things via connections he’d made in the music business, tickets and merchandise that he would pass on to anyone else interested as his own love of rock and roll was on the wane, the jazz years beckoning. I was a glad recipient of these treasures. This was an instantaneous legacy reward of that episode in the music business and by proxy for me on the trickle down, some comfort amid the grief of the loss of something and some things.

One day he handed me a ticket and asked me,

‘is this of any interest?’

It was a ticket to see Hawkwind at Manchester Apollo.

I had a vague idea of Hawkwind, some very basic info about them and some strong images of their Space Ritual that I’d seen in a book of my Dad’s about rock concert photography, with figures that seemed to wriggle and writhe, fuzzy musicians and dancers with long hair and flared skin and wires in strobe blue clouds but I knew nothing about the music at all, not a thing I could hook onto so I was intrigued and lured by the thrill of attending this concert on my own.

As big as the world is, the universe is always in the palms of our hands.

Hawkwind: The Space Ritual.

The 4 strings of the railway lines to and from Manchester centre at Heaton Chapel Station, crossed by the Heaton Moor road, a bass line.

So there I was with a ticket to see Hawkwind, a band I didn’t know, who I’d never heard before who were alluring and edgy for reasons I had yet to understand. This was 1984 and there was no easy way for me to find their music as I didn’t then know of anyone who knew them well. They were a name seen on the back of some jackets, a patchouli and squidgy black hash aroma band but no sound that I or anyone in my immediate vicinity knew then. None of my mates were keen to join me so I was on my own on this escapade. I caught the 192 bus to Ardwick alighting opposite the Apollo theatre. Before me was a messy rabble of denim and leather and silky floating things caught on thorns and hairy thickets, all bustling around the doors of the venue.

I wandered into this unknown and immediately saw people who were fantastic and terrific. There were many shapes of characters forming in the mass of bodies at the entrance to the auditorium. I moved inwards surrounded by huge and wild people who flowed outwards in coils and aromas and billowing patterns. Some I recognised as faces from Stockport, the four Heatons and Reddish, the mythical names murmured and whispered around. As I mooched in looking for my seat, to my surprise I noticed a kid from school known as Goody, so I strode over and said hello. He was sat with a cool looking lad with an almost jet black spiked mullet hairdo, a kid called Muppet who I subsequently became good friends with, also a bass player.

I went to the bar with Goody and Muppet. We stood around looking young and awkward no doubt but it felt so cool. I was able to see the people more clearly, a very interesting selection of freaks. Many looked like they were from the pages of books I had borrowed from my Dad such as The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test, Hells Angels and Fear and Loathing, some Freak Brothers too and lots of smiles, women with electrified hair laughing and men with creased beards grinning the good vibes all around me.

I was clueless about Hawkwind. I had been to plenty of gigs before but this felt different to all of them, it felt like a travelling circus had come to town and we were all part of this circus, even me almost an alien in this scenario yet invited and welcome.

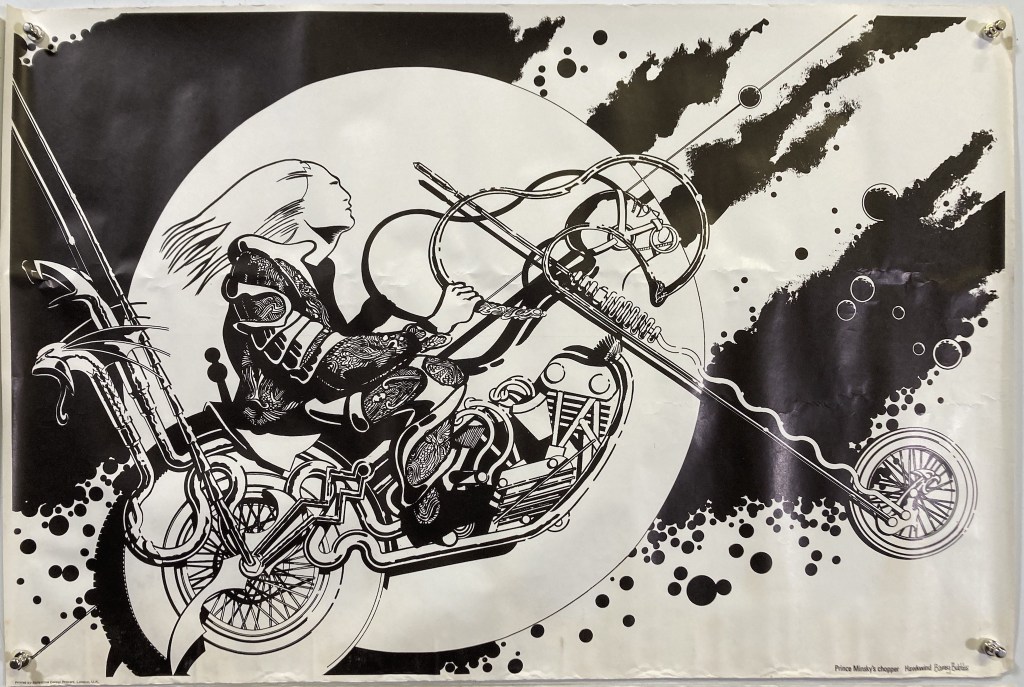

Barney Bubbles, Prince Minsky’s Chopper, 1972 Michael Moorcock inspired poster sold at early 70s Hawkwind gigs.

The band appeared through a wallof dry ice and drums, a drug of noise and lights and bodies and everyone there was identified as this sound in a singularity as the paisley curled tapered edge jet propelled sonic attack doubled back to anatomic foundations in the leviathan power of the bass.

The noise was intense like a an aircraft engine, a Lockheed Starfighter crashing into the seating rows splashing chunks of hot metal like sea spray, a massive plateau of doughy stone bass behind the sparkling shards. It was elemental and brutal. Even in memory it is exhilarating, the unknowing of the songs enhancing the magic amid the stroboscopic blur of images. It was all very ritualistic, a ghost danced swelling in my solar plexus that infiltrated my nervous system and possessed me, levitating me.

I was in a row of seats to the left of the stage about six rows back from the front but I couldn’t see much detail through the dry ice and strobe lighting and the tribal drums and chants. There was one very vivid presence though, a lanky figure at the edge of the stage wearing a skin tight bodysuit but looking naked, with a red spike of hair protruding from his head. He was singing sometimes and carrying a saxophone, occasionally honking it. Who the? What the? How and why? I wondered, silently small and paralysed in this Hawk wind tunnel of sound, surrounded by grooving bodies, wild hair and shoulders.

After the concert, once I’d come down from this very natural psychedelic experience, the earth I landed on was transformed as I was transformed, physically and mentally, a destiny becoming apparent.

That feeling of the concert being a communion and the music being part of a ritual which involved all the aspects and transmissions between audience and act was something beyond the received idea of a concert. This was a travelling fair as old as time and older and I had danced myself right into it.

Nik Turner performing with Hawkwind, dressed as a frog. 1974.

In time I found out that the crazy sax dude was Nik Turner who I quickly became obsessed with and as the year unfolded I went to see his other band, the splendid punky chaotic collective known as Inner City Unit. Then there was the everpresent Dave Brock,the founder, lock groove churner and so called Captain of this crew. I never saw him whole at the Apollo gig, he was a shadow in the strobe glow but at subsequent gigs I could see his stage role was never front centre but his presence in the music was fundamental. Once I had started to learn about Hawkwind the more I needed to know. I listened to albums from different periods and line-ups, from their prodigious primitive synth and riff driven early records, the heavy clanging space sound of the Lemmy and Michael Moorcock years, the Post-Punk angles and delicious lyricism of the Robert Calvert fronted years then morphing into a more rocking sound with Ginger Baker drumming, then regenerating again in graded iterations into the professionally ramshackle punkadelic outfit that hit the Apollo in early 1984, made up of older band members, the impressive guitarist Huw Lloyd Langton and ‘the cat with the silver face’ as Jimi Hendrix called him, Nik Turner.

The music is a vessel for the Hawkwind vibe, consistent in all of the recorded songs I heard in different encodings, as if the purpose of the song is to present a newly processed variation of the open source Hawkwind genome. It’s all about the feel and the transmissions and on record that is presented in songs which work as shrines to the motifs mixed down from long jam sessions. There’s magic in those lock grooves caught on tape.

Another thing I noticed, generally Hawkwind songs weren’t about the usual rock and roll obsessions such as lust and love and didn’t seem to hinge on the exploitation of young people. I think this is another reason people dwell there once the music has grabbed them. The Hawk vibe is edgy looking from the outside but is a generally safe space for all who enter, the cosmic has an equity that the art naturally settles into, like a bullfrog happy in it’s own sinking skin.

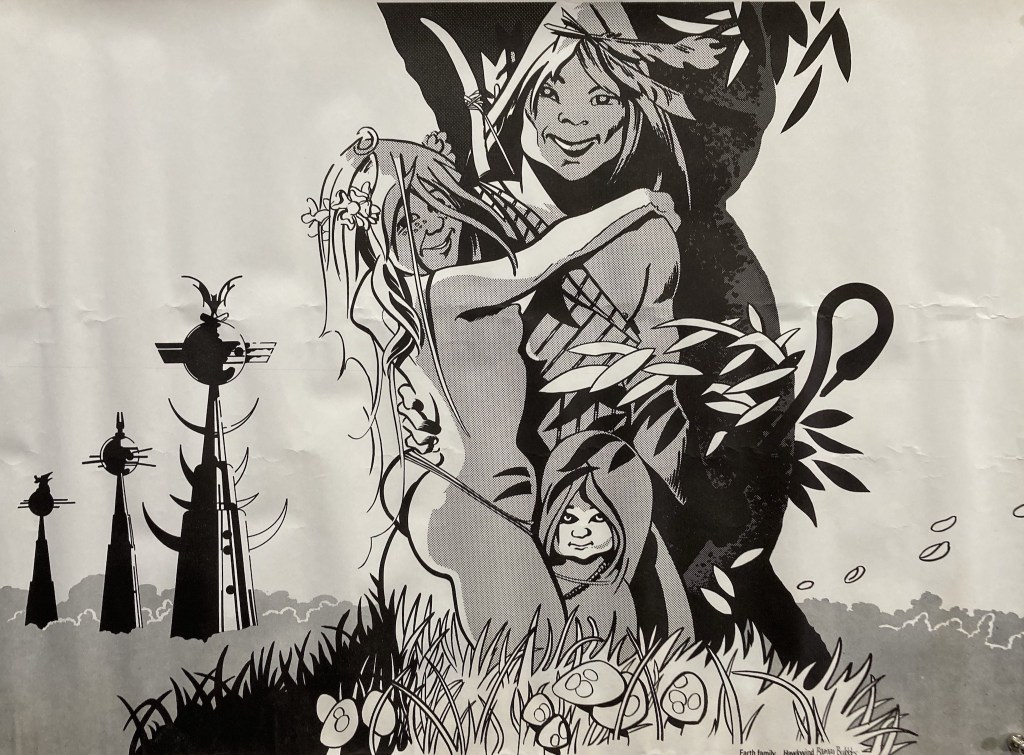

Earth Family by Barney Bubbles, Michael Moorcock inspired poster sold at early 70s Hawkwind gigs.

Hawkwind seemed really old compared to most bands around even though they weren’t that old then, but the little bits I was picking up about them cast them as veterans of the road and that was 1984 and they had formed in 1969. They are still going now in some form, 55 years and counting. Rock and Roll wasn’t meant to get old but Space Rock is a continuum. The fanbase has a community identity seasoned over many years with a back catalog of lived experiences, vagabonding days and outlaw nights rebelling against whatever they found obstructive, a way of life shared by the fans and the band and finding a most enduring expression in the familial and sometimes fraught relationship that Hawkwind had with the Free Festival scene, which was at this stage a social and political battleground, the festival goers the ideological enemies of Thatcherism.

Fossicking and grundling to catch a fish of gold and a bee and a cold.

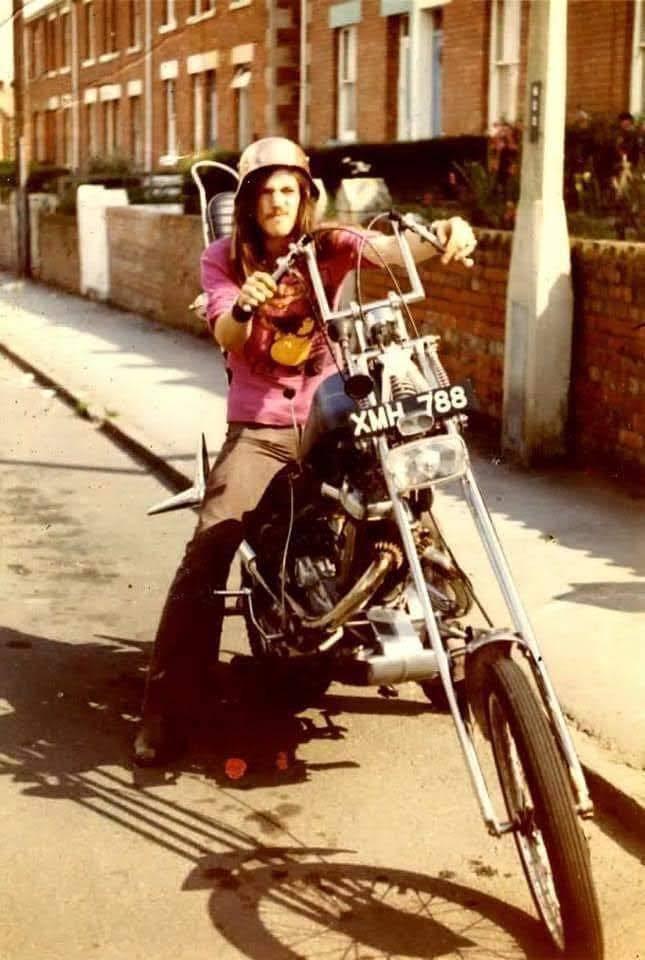

By the autumn of 1984 I had turned 16 and landed at Stockport college where I met many people and a fair few were Hawkwind fans. I met a motorcycle loving, sharp witted young man called Gunter in an Environmental Science class, he lent me some tapes known as the Weird Tapes which were Hawkwind related rarities and offcuts of mysterious origin. A few months later I met a lad from Heaton Moor called Jonathan Anderson, known as Jock then but I’ll call him John here. I’d seen him around the Heatons often, he stood out as he had a really good looking motorcycle and he dressed in a fusion of 1960s Californian and British motorcylist styles with Hawky and Motorheady flourishes on his bike and his gear, like he’d stepped off the pages of a New English Library pulp novella with a San Francisco twist. I had decided that I was going to try get to know him and his associates and so I did, eventually meeting him formally at Stockport College Students Union Christmas party, an epic afternoon of pure hedonism. We hit it off immediately, we talked about Hawkwind naturally and then about Scotland as he was clearly very Scottish, and it turned out he was from Hawick in the Scottish Borders, my Grandmother Lillias Dalgleish Welsh was born in nearby Selkirk so we had some kind of kindred connection, a Hawickwind vibe.

John taught me so much about the band and their many variations and proliferations that fused and aligned around the music, as well as helping steer that raw and wilder version of me onto an ethically sound road and connecting me to some incredibly influential people who became friends and helped me to grow sideways through time.

My mate John Anderson, how he looked when I met him, on his z250 chop in the mid 80s, and more recently with Sally his stunning Bay Area style Harley Davidson chopper.(images © Jonathan Anderson.)

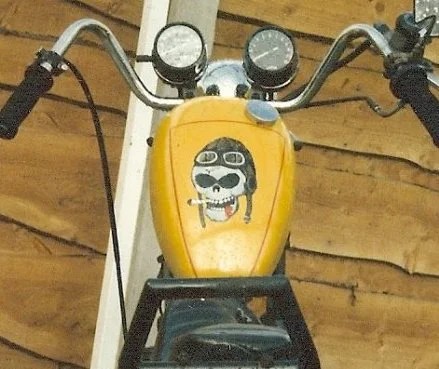

Tank I painted for John’s z25o chopper. 1985.(image © Jonathan Anderson.)

John told me the greatest of all revelations thus far and life was never ever the same since.

This revelation of holy grail like resonance vibrated the very stones we stumbled on. Heaton Moor Road, that bassline of a road that crosses the four string train lines was a holy site in lore. John told me that Lemmy from Motorhead, the onetime Hawkwind legend whose playing defined the classic Hawkwind sound and who sang lead vocals on their most famous song Silver Machine, had lived in a squat on Heaton Moor Road in the 1960s.

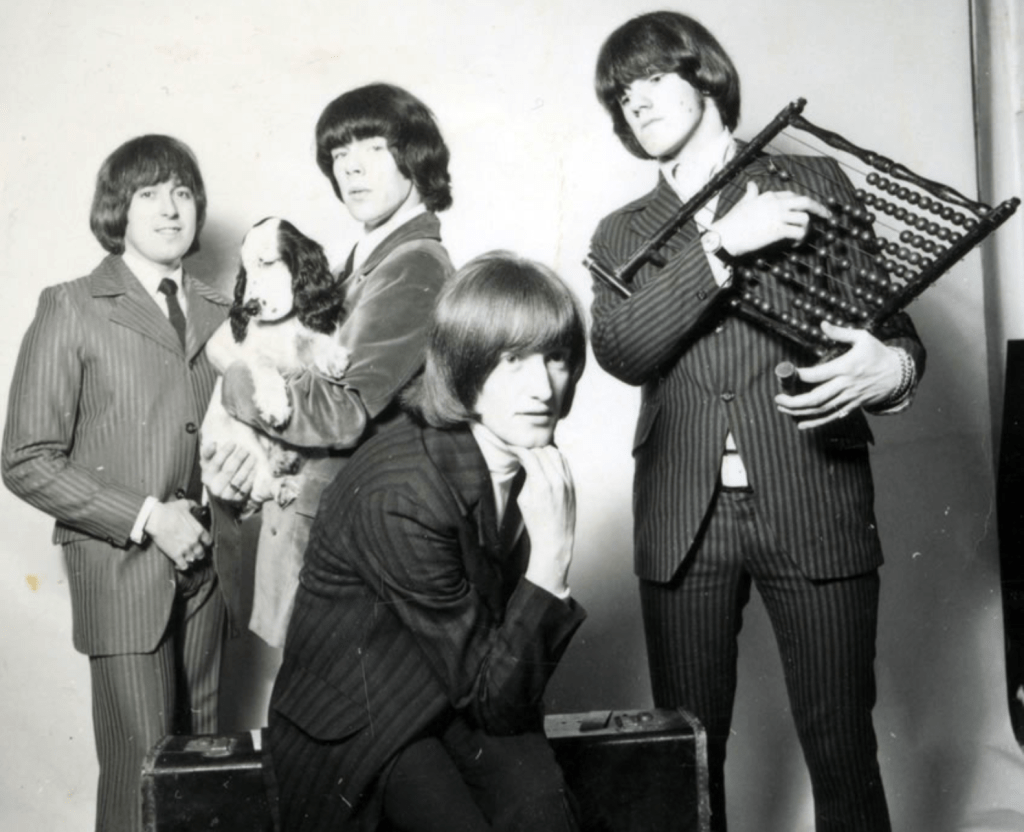

Lemmy had been a busker in Mersey square in Stockport town centre and was a part of the Manchester ravers scene. He played guitar in The Rainmakers, then from 1962 to 1965 he joined the Motown Sect. When they split he joined the Rockin’ Vicars who toured all over Europe and had a reputation as one of the best live acts in the UK.

Lemmy plays abacus in the Rockin’ Vicars, they wouldn’t let him play the Spaniel.

Lemmy posing on a friend’s chopper, possibly in Shaw Heath, Stockport, according to unconfirmed reports, late 60s.

One of the New English Library Biker books.

John (Jock) Anderson is an historian and collector of stories and insights, he’s also a bass player, Rickenbacker of course. John knew people who had known Lemmy back then in Stockport. John enlightened me to the subcultural history of Heaton Moor, some of which was still living in our faces in certain corners where there were squats of renown and many houses of repute and plentiful characters with twinkled eyes and laughter lines drawn back to the countercultural 60s and 70s. There were times when, with the roar of motorcycle engines heralding the spectacle, if you squinted enough and breathed in the exotica then 1980s Heaton Moor felt like how I imagined 196os San Francisco at Haight Ashbury.

The Hawkwind concert was a pivotal event which generated connections. I met so many people through my interest in this strange and welcoming community. At Stockport college I reconnected with an old friend I hadn’t seen for years, Dimitri Oldenburg, the son of my Dad’s mate Jan the Night and Day Cafe owner. Dimitri was loquacious and hilarious, a very creative young man and who later became an essential mover in the early days at Night and Day, making vegetarian pies to sell in the old cafe and bringing in his many friends from all over the conurbation. He was a massive Velvet Underground fan and quickly fell into the Hawkwind habit, particularly those early records with the Sister Ray style lock grooves. I met this one glorious Heaton Moor head called Simo, a talented anarcho-punk rocker, a film and music maker who loved Hawkwind and Motorhead and who lived life like a performance artist, deeply commited to surrealism. Simo and Dimitri became very good friends too, the social scene was like a free festival at times, these were the rolling people.

Dimitri Oldenberg and Simo, Gary Yeahbutwhat (he changed his surname from Simpson) in search of space. Both gone too soon and sadly missed. (images © David Moss and Richard O’Neill)

Simo was the chaotic frontman in a band called Naff with another talented and surreally chaotic young man, my old school friend Herman on synths and samplers, who a few years later opened a head shop in Manchester centre called Herman and the Hippy (which morphed into Dr Herman’s and still exists in town) before buggering off in 1989 to explore the world and being right there and then in the here and now at the beginning of the Psy-Trance scene in India. There was a laconic dude with azure eyes and a transatlantic accent called Wally on drums and a most genial giant on bass, the musically prolific polymath and authentic space nomad Mr Dibs.

Dibs moved on to the Space Rock band Krel who were influenced by and played with Hawkwind, and then after Krel he formed Spacehead, furthering the cosmic exploration. Quite naturally he followed in Lemmy’s bassprints first as a roadie and by 2007 he became bass player and front man in Hawkwind. He brought new energy to Hawkwind, fusing and enthusing his love of the back catalog, particularly the Calvert era, with a future embracing musicality and attitude. It was an exciting time for the band during his watch. Now he’s playing in Hawklords which originally was the name for a re-imagining of Hawkwind in the late 197os and has since become a band where ex Hawkwind members have gathered as refugees from the starship. Hawklords has over time included original founding member Nik Turner, the stalwarts Harvey Bainbridge and Dead Fred who were all in the band at that first Hawkwind gig I saw and many more space vagabonds and Hawkwind survivors. The latest version of Hawklords is a tight three piece space rock band with songs that feel like some the best of Hawkwind of yore while sounding fresh, punky and progressive. The current line up is Jerry Richards, Dave Pearce and Mr Dibs .

Dibs and Spider, on his bus way back in the early 90s. (image © Jonathan Hulme)

Mr Dibs and Dead Fred in Hawkwind mode. 2016. (Image: © Lorelle Fisher)

As time flows by some things change considerably but many of those hardcore characters, the friends I made while charmed by the strangeness of Hawkwind have grown and evolved and flourished but have also kept faith with the lifestyles and beliefs they held in the 1980s. Still riding, still travelling, still freewheeling, still stargazing and spanking planks and throttling strings and stringing throttles and making things howl and growing things, bending metal and hammering keys, forging music and crafting the good times, letting them roll.

My northern vista starts in Stockport at the steep rise where the Roman legion stalled at Tiviot Dale as the Mersey forms at the base of Lancashire hill where my Dad had his Crazy face shop for several decades. My friend John from Hawick told me that Tiviot dale was named by the Scots who camped over there in 1745 with Charlie Stuart’s army, much like the Roman army had done 1700 years or so before them. It was a misheard misspelling of Teviot Dale, a beautiful valley south of Hawick and Selkirk where our ancestors dwelled.

‘Deep into distant woodlands winds a mazy way, reaching to overlapping spurs of mountains bathed in their hill-side blue. But though the picture lies thus tranced, and though this pine-tree shakes down its sighs like leaves upon this shepherd’s head, yet all were vain, unless the shepherd’s eye were fixed upon the magic stream before him‘

Herman Melville. Moby Dick.

Heaton Moor road is the bowed spine of a leviathan steppe, a rich cultural area steeped in Rock and Roll history, shaped like an Oud with those train line story strings pulsing a process of passageways scored in years of intersecting basslines and engines, underground streams feeding the sacred Mersey.

Time is a tangle, a clumpse of coincidences, a thicket uprooted rolling downhill to water. The wider spaces and ancient murky ways around South Reddish and the Heatons, the stream bank trails and ridge paths, slurry dips and steep meanders, the Roman bisection of Manchester road at the Merseybeat confluence chamfered by the A6, a river of tar turnstiled at Wellington road and those train lines crossed by a one note bassline. The Heatons are defined by lanes and lines where cultures form on the shade of artery walls, mosses grown in the shade of trees.

Heaton Moor is a bass line

four strung train lines

Asyndetic note lines

and the pause at the heart of engines.

Music and Motor, Jonathan Anderson collection. (image © Jonathan Anderson.)

Many thanks to John, Dibs, Herman and all the cats.

Hawkwind, inspired and energised, playing Nik Turner’s ‘Watching the Grass Grow’ Stonehenge 1984.

More Hawkwind from 1984, from Ipswich on the Earth Ritual Tour, capturing that same ritual intensity of sound and light that I witnessed.

And here a very good song.

*featured image, The Fanon Dragon Commando by Barney Bubbles, Michael Moorcock inspired poster used to promote Hawkwind‘s 1973 single Urban Guerrilla

Leave a reply to D-Moss Cancel reply